The Tempest is my favorite Shakespeare play. It’s the play that made me fall in love with Shakespeare, which means it’s right up there with all the other things that made me fall in love: Seven Samurai (Japanese movies), Sasha and Digweed’s Communication (techno), Maverick, Cheyenne and Sugarfoot (westerns), Myrna Loy (Myrna Loy) and Sheila Tagrin (girls). It's also the play I directed, in the dark backward and abysm of time, when I was a senior in high school. As I have so often had occasion to remark these days, boy, do I have a great future behind me.

I know the script of this play the way I know a Beatles song -- I may not be able to recite all the words on my own, but I will be word perfect once the song starts playing. Which is why it’s impossible for me not to be annoyed when Argiers becomes Algiers, the still-vexed Bermoothes turn into the still-vexed Bermudas, the line “Oh what a blow was there given!” is missing its punchline (“An it had not fallen flatlong.”) and my favorite WTF line in all of Shakespeare, “And most chirurgeonly,” is nowhere to be found. This is also why it’s impossible for me to be objective about this play, so what follows is not so much a review as a collection of thoughts about the experience of this particular production.

First thought: nice opening. The play begins with a shipwreck scene, but the production begins with Prospero, who’s sitting stage left reading a book from the moment the house opens. It's a great conceit: here's somebody with his head in a book all the time; no wonder he lost his dukedom. And that was 12 years ago. Guy hasn't changed a bit. Only when he’s ready does he don his magic robe, put on his belt of power (shades of Wonder Woman and her magic belt), take up his staff, and conjure up the storm which will cause that opening shipwreck scene. At which point we’re reminded that Sam Mendes is directing this play, since the shipwreck scene is marred by the same annoying effect that marred last year’s Winter’s Tale: any time there’s an aside, the actors all freeze, the stage goes dark, and a spotlight hits the commenting actor. Then the action starts up again, only to stop with the next comment; and then it begins yet again only to grind to a halt with the next aside. It’s so jerky and frustrating that it’s impossible not to believe that the single most formative experience of Sam Mendes’ life is his struggle to drive stick.

The next, oh, 20 minutes is the longest single exposition scene in Shakespeare. The story is, he wrote it to win a bet with Ben Jonson, who kept making fun of the fact that Shakespeare never stuck to the Aristotelian unities of place and time.

JONSON: If you wrote the Agamemnon, you would have staged everything from Aulis to the Trojan Horse before getting to the homecoming. You and your mouldy tales. You put Father Time in Winter’s Tale, and Pericles takes place over what, twenty years? Man, you couldn’t do single set and real time if your life depended on it.

SHAKESPEARE: Oh yeah? Here; read this. It’s called The Tempest.

JONSON: Oh my God! The second scene is nothing but exposition! And not even interesting exposition.

SHAKESPEARE: Yeah. See how boring single set and real time are?

And that’s the challenge when doing this play: how to sugar the long Prospero speeches so that they don’t put everybody to sleep. (And it’s not like Shakespeare is unaware of what he’s doing, either; Miranda’s line “Your tale, sir, would cure deafness,” could be spoken by anybody in the audience.) So what does Mendes have Prospero do? Blindfold his daughter so that, in effect, he is just a disembodied voice, and then rattle on while she sits there like a prisoner waiting for the firing squad to arrive. I’m still trying to figure out the whole blindfolding motif, and it is a motif -- Prospero covers Miranda’s eyes a couple of times in this production, like he’s protecting her from something. But what? I can understand covering her eyes when Caliban shows up, but when you’re giving the premise?

PROSPERO: I’ve led a rather interesting life; would you like to hear about it? Good; let me blindfold you.

MIRANDA: Whatever, Dad.

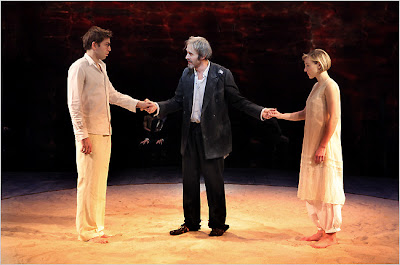

All I can think of is that it's about two things: his magic, and the fact that this particular Prospero has no idea how to deal with real people. As far as the magic goes, I can buy that Prospero creates the shipwreck. But if you’re going to set him up as somebody who can control not just the winds but the other characters on stage, if you're going to make the man a puppeteer, then you have to be very precise about (a) who the puppets are, (b) when and if they can ever act on their own, and (c) why the puppeteer is manipulating them. That clarity is missing here. Lenane’s Prospero appears to be manipulating everybody, including the bad guys. I mean, Antonio and Sebastian are natural plotters; it’s only natural for Prospero to use his arts to make sure their plotting fails. What is not natural is for Ariel to hand both of them daggers so they can attempt to commit murders which will then be prevented. It’s beautifully staged; Ariel walks past them and the daggers he hands them look like they have always been in their hands. But it’s troublesome when you think of the puppeteer angle. It’s one thing to say, “I know you will try to commit murder, but I am going to prevent you,” and quite another to say, “Here’s a couple of daggers so you can try to commit murder so I can prevent you.” It makes the game look rigged from the start. I mean, if Prospero can control everybody to this extent, then you’re watching an argument against the existence of free will, not a play. Or an argument about an all-powerful figure who makes people commit sins so that he can indulge himself in not just preventing them but in forgiving the sinners. After, y'know, an appropriate amount of spiritual torture. I don't know about you, but to me this is both dramatically and theologically unsound.

I used to do the "You are three men of sin" speech as an audition piece,

so don't get me started on this guy's Ariel.

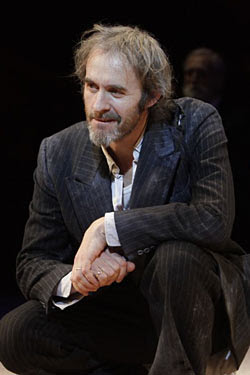

It’s also untrue of this production, which is about vengeance and forgiveness. Almost everyone who’s not being tested or manipulated in a center ring of sand sits on chairs in an upstage pool of water and waits their turn to go onstage, staring off into space while they wonder if the Equity healthcare plan covers the kind of pruney foot rot that infected half the grunts in ‘Nam. The constant presence of actors waiting to go on gives the impression that Mendes is staging a Brechtian exercise in presentational ethics, where everything has a pointed moral and everyone has a lesson to learn. Especially Prospero. Judging the production backwards, the naturalism of Stephen Dillane’s underplaying, once the opportunity to forgive has been presented to his character, stands in stark relief to the shouting hand-waving over-emphasizing hammyness of his early scenes. I kept asking myself “Why is he over-acting like this?” and of course, by the end of the play I understood exactly why: to make a contrast between Prospero the avenger and Prospero the forgiver. The problem I had with it is that shouting is a technique, not a character revelation. When he's observing -- like Jacques -- Dillane's Prospero is in his element, speaking naturally and pointedly. But when he's talking to other people, he's a completely different person, and unfortunately it looks like he's a completely different actor as well. It's a valid and fascinating choice to make Prospero the socially inept twin brother of Jacques, but I feel like I'm making an after-the-fact excuse by thinking of Dillane's performance this way, because while watching it, I didn't know what to make of it. It's like he was playing an acting version of vengeance versus forgiveness: the rarer action is in underplaying than in hamming it up.

But like I say, it’s impossible for me to be objective about this play. Or to see it fresh, for that matter. Even the moment that made people gasp -- Caliban’s first entrance -- reminded me of the same entrance, done in exactly the same way, from the 1974 Public Theatre Tempest with Sam Waterston as Prospero, Carol Kane as Miranda, and Randy Duk Kim as the best Trinculo I have ever seen. (And God, what a weird production THAT was.)

But I will say this. If everything Dillane did as an actor was designed to make his delivery of the epilogue poignant, simple, and profound, then he totally succeeded.

Homeless man helps color-coordinated ingenues find true love.

2 comments:

OMG, I am supposed to attempt to teach this one in April....yikes! I need pointers, friend.

pointers

Post a Comment